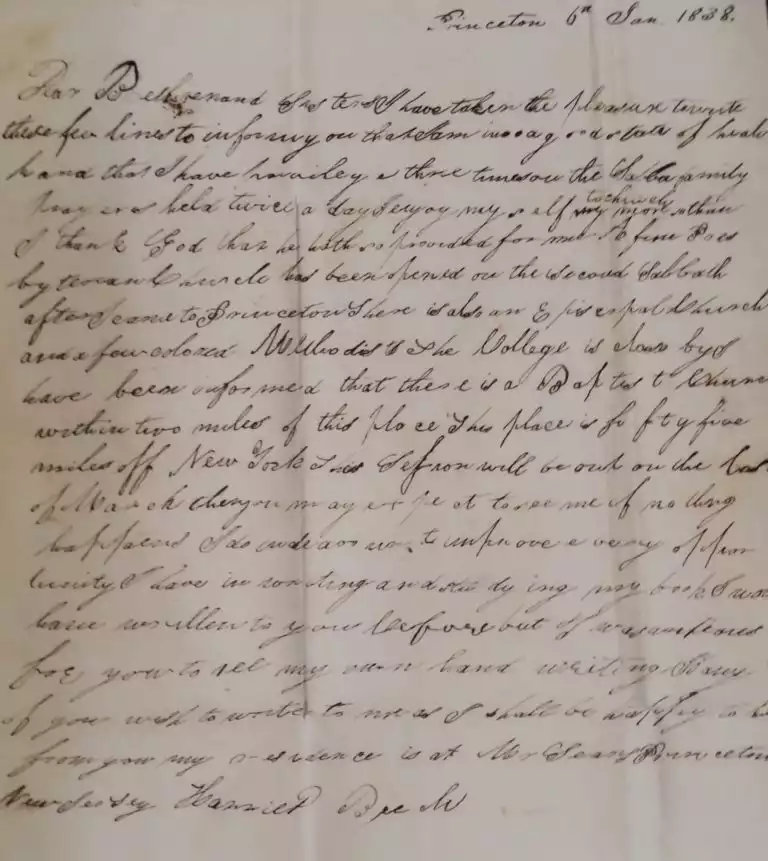

“I do endeavor to improve every opportunity I have in writing and studying my book. I would have written to you before but I was anxious for you to see my own handwriting.” Harriet Beech, a free African-American woman living at the residence of Mr. Searcy in Princeton, wrote in 1838, in a letter describing religious opportunities and life in her new town. Looking for clues to unlock the past and what it was like to be a part of the community, seventy-odd attendees came to the library recently to see unique historical documents like this letter in person. As part of the Princeton & Slavery Project (which has gotten national attention in part to a recent New York Times article), the library hosted archivists from the Historical Society of Princeton and Princeton University who brought several original documents from their collections and set them up to be examined up-close in the second floor Discovery Center.

Uncovering history through glimpses of everyday life and finding the parts of individuals’ stories which resonate today in the twenty-first century, is key to the research of the Princeton & Slavery Project, led by Princeton University history professor, Martha A. Sandweiss. What she imagined eight years ago would be “a one-off class” examining town’s relationship to slavery has expanded in 2017 to encompass a community-wide series of programs and events, a sold-out four-day symposium and a research website presenting more of these primary documents. Thanks to the efforts of our humanities fellow, Hannah Schmidl, and support from the NEH, Princeton Public Library is an active participant in the project, hosting a variety of events and activities through November.

At the library event, University Archivist Dan Linke spoke of the three key elements to thinking about slavery and Princeton’s story: people, power and money. While Princeton University as an institution never owned slaves, individuals who were faculty and administrators did benefit from owning slaves. As the Ivy college which had the most southern attendees, some students’ families were slave owners. The wealth, influence and position which benefactors and educators derived from these activities benefited the institution. “The first nine presidents of Princeton all, at some point in their life, owned people,” Linke said, pointing to history in our town as part of a bigger narrative playing out in towns and on campuses across the country. The November symposium, activities and exhibits focus on looking back and looking forward. Linke urged those who were curious about where such studies lead to visit Brown University’s Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice as one example of a complex examination of issues that has grown from similar efforts.

Want to see more history? Walk down the modern, newly re-imagined second floor hallway in our library building, through the books in the History neighborhood. You’ll be facing the Princeton Cemetery as you approach the Princeton and Slavery exhibit on display in the Princeton Room, which contains our Local History collection. Consider the documents from the Princeton & Slavery Project, and the related events, research and discussions swirling around town, formal and informal. These stories are being told as history is uncovered and brought to light locally and in the national spotlight.

Letter by Harriet Beech, 1838 / Collection of the Historical Society of Princeton